In 2002, Sylvie Déthiollaz and I were asked to imagine something that could entertain young children within the framework of a science fair. The fair was to be held in the Museum of the History of Science in Geneva, a neoclassical 19th century villa on the edge of Lake Geneva, which sits in the middle of a beautiful park. We had been thinking up activities for children for a couple of years already, which invariably involved coloured beads which we threaded onto a bit of wire to illustrate a protein's sequence of amino acids. We then folded the wire to give an idea of what a protein's 3D structure could resemble. The activity was always very popular, although frequently used as a spot where parents could leave their children while they wandered off to see something else. Besides our growing distaste in being used as a nursery, we couldn't face beads and wire anymore either and, quite naturally, we suggested writing up a tale for children instead. And "journey into a tiny world" was conceived.

Although this article celebrates the publication of the English version of "journey into a tiny world", the original version - Globine et Poïétine sur la piste de la moelle rouge - was written in French five years ago. Once the idea of a story had been agreed upon, the next step was to decide what we were going to write about, and then write it. The tale had to involve proteins; that was our only dictum. The rest was up to us.

The idea of a journey into the recesses of a little girl's body arose quite naturally. However, there had to be a reason for such a journey. One that made sense. It wasn't long before we imagined that the little girl had to take medicine - a protein - that would lose its way inside her and, in so doing, get the chance to visit numerous parts of her body as well as meet other proteins. Our hope was that children would discover that an organism is full of different kinds of protein, which each have a specific job to do. Sylvie had just finished an article on EPO (erythropoietin), a protein which has the capacity to stimulate the production of red blood cells in the bone marrow. This became our starting point.

Little did we realise though that the choice of something so specific would put certain restrictions on our imagination... For one, EPO could not be swallowed but only taken by injection. Secondly, several weeks into the creation of our tale, Sylvie announced that the little girl was far more seriously ill than we had imagined! It didn't change the course of our story though... And Sylvie and I moulded our characters, weaving them in and out of situations according to our fancy. It was a delightful experience.

You may wonder how two people can write together. There is no rule to how this can be done. But as far as the making of this tale goes, I wrote from my kitchen, while Sylvie wrote from the office. We wrote up the different chapters independently and then compared them. To our constant astonishment, our minds glided along the same paths and most of the time we were thinking along the same lines, which made things relatively easy. Sylvie then sifted and sorted the ideas and adventures of our molecules, keeping the best parts and discarding the poor ones. As a result, within a couple of months, we managed to produce the French version of the tale.

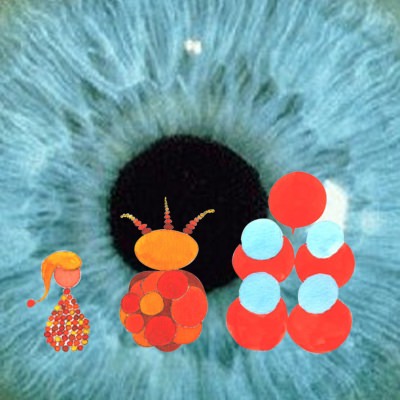

"Globine et Poïétine sur la piste de le moelle rouge" was the title. It is the story of Poietin who careers around a little girl's body - Lily - with Globin, a friend she picks up on the way. Together, they experience great adventures discovering what it is to look through an eye, to sit on the edge of a wound or to watch a heart beat, while meeting other proteins like Actin, Myosin, Orexin or Insulin. Following a sequence of exploits, Poietin finally finds the bone marrow she needs, from where she will be able to stimulate blood cell production and save Lily's life.

During the science fair, a modest set with two red armchairs, a carpet and a white canvas mounted on an easel - on which we projected the illustrations which are now part of the published book - was arranged in a far corner of one of the villa's drawing rooms. We would have liked a local artist to do the illustrations for us. When we were told how much it would cost, it became obvious that we would have to rely on our own artistic talents. So Sylvie and I grabbed a pencil and a paintbrush and produced our interpretations of the various characters you can find strewn through the book. Despite a solid background in biology and, consequently, a sound understanding that proteins have no eyes, mouths, arms or feet, we decided that if we wanted to give them some kind of a literary life, this was one of the ways to go about it.

The tale was read several times over a weekend by two actors who managed to infuse life, beauty and magic into the story. And we will always remember the little girl who stayed to listen to more than one reading and who, by the end of the day, had learned some of the lines off by heart. Meanwhile, she had managed to drive her mother - whose only wish was to head back home - round the bend. The whole thing turned out to be a success, and a number of parents asked us whether we were thinking of making a book out of Globin's and Poietin's adventures. We thought it was a good idea, and the book was published in French in July 2003. And four years later, the time and energy was found to translate the tale into English.